Street kids, my regular companions as I waited for my cousins outside the old Eros Cinema, across from Churchgate Station, Mumbai 1996. Photo by Mark Mauchline.

India has always been a part of my identity. That may seem an odd statement when looking at me, someone whose outward physical appearance resembles more his Scots father’s roots, than a mother born in the middle of the subcontinent. But, I have been drawn to her ever since our mother decided to take my younger sister and I on our first exploration of her birthplace as children. And deep down, I’ve always wondered what might have been if my mother had not boarded a boat in 1950, and immigrated to Canada. Obviously, she would never have met my father, and so the “me” is purely hypothetical. But, what would life be like for the Indian version of me, if there ever were one?

The 2016 film Lion is the story of “Saroo”, Sheru Munshi Khan, a 5 year-old Indian boy who becomes separated from his older brother at a train station south of their home in Khandwa, Madhya Pradesh while his brother is searching for coal to pilfer, and later barter. A tired Saroo is left to sleep on a station bench, thus beginning a series of cascading events: Saroo is accidentally locked in a train; he is transported 1500 kilometers away from his Khandwa home to Calcutta; he is befriended by an unscrupulous couple, who seem intent on selling him into slavery; he manages to escape, and is found by an adoption agency. Ultimately, he finds a new adoptive home in far-away Australia. Twenty years later, he begins a search to find his hometown and family.

It didn’t take long once I began watching the film Lion, to realize there was something very familiar to me about this story, and more specifically, the story’s initial location.

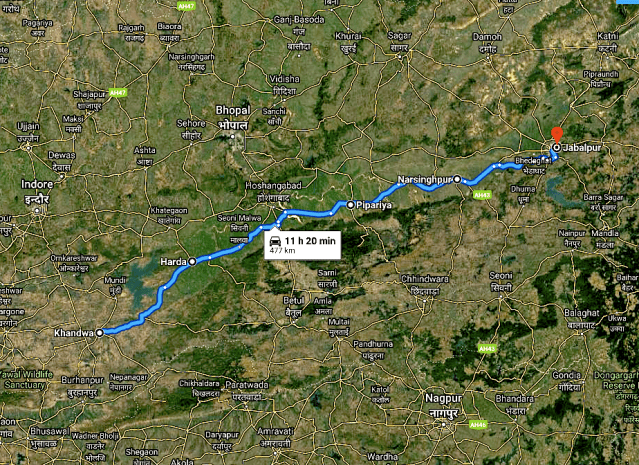

The route of my impromptu bicycle trip.

In December 1997, a good decade after Saroo and his brother had left home, I got off the Howrah Mail Indian Railways train in the early morning. My Bombay cousins and I had boarded our second-class carriage the previous night in bustling Victoria Terminus, VT for short. The train was packed, as often is the case on the spider web network of aging rolling stock that is the world’s largest railway network.

We were heading to my mother’s, and their father’s family home in Jabalpur for Christmas, before moving on to Goa for a bit of an Indian beach holiday. I decided to leave the train early and add a short 3-4 day bike ride into my itinerary. Based on the Indian Railways schedule, Khandwa, with its earlier part of the morning arrival, seemed like the perfect hopping off point for a spin through rural Madhya Pradesh on the way to “Jub”.

The Google Earth view of the railway station in Saroo Brierly’s hometown. Note the overhead walkway at the north end of the station platform.

The platform was quiet, almost deserted. I may have been the only one departing here on the day. Thinking back, I can’t imagine it was much different from the platform in Burhampur station, where Saroo had fallen asleep almost ten years earlier, became separated from his brother, and began his long, roundabout journey to return home. After waving goodbye to the cousins, I exited the station via the overhead walkway to the quiet street outside, and started pedalling towards the town of Harda, and a government guesthouse I would spend the night in, courtesy of the position held by my retired uncle in the Indian Civil Service.

For the better part of the next week I travelled on state roadways through primarily agricultural land, passing road signs with names I recalled from stories I had a heard while growing up. They involved my young Commissioner-to-be uncle driving in an open top Jeep, sometimes with my kid-sister mother in tow as he did his rounds. I passed Itarsi, Pipariya, the jumping off point to the hill-station town of Pachmarhi, Narsinghpur, the location of the infamous showdown between the ‘Thuggee” criminal tradition and India’s 19th century British colonial masters, and the turn-off for Seoni. A warm winter sun, and a subtle sepia haze accompanied me as I followed the rift valley of the Narmada River, winding its way from east to west, across the northern extreme of central India’s Deccan Plateau.

Eventually, with the help of internet tools like Google Earth, Saroo finds visual clues which eventually lead him to his hometown. Up until now, he has futilely searched for “Ganestalay”, a mispronunciation of the Khandwa neighbourhood Ganesh Talai where he had lived. He reconnects with his mother and remaining family, learning that his brother was struck by a train and killed the night they were separated, and that his actual birth name was “Sheru”, meaning lion, something he had been mispronouncing his whole life. The film ends with scenes of the real life Saroo introducing his adopted mother to his birth mother. Saroo Brierley’s amazing search for self had come full circle.

Typical Indian Railways rolling stock.

Madhya Pradesh State, India, 1997.

Photo by Mark Mauchline.

While watching the film Lion, the name of Saroo’s hometown Khandwa was a place I recognized, but I wasn’t sure why. It gnawed at me to the point where, like Saroo, I used Google Earth, and the Indian Railways’ route maps and timetables to figure out that I had not only recognized the name of his hometown, I had been there, and ironically, by train.

I have never been challenged with finding the origin of my immediate roots, or faced the resulting needle in a haystack search undertaken by Saroo Brierley, but I still feel an affinity with him.

My search for connection, my curiosity with my mother’s origins, that impromptu bicycle trip from Saroo’s hometown ten years after his story, the story of Lion began, was to try and experience, live, and feel some of the area I had heard about in family stories concerning my mother. It is a connection never far below the surface, which remains ever present, a bounding pulse, which I continue to feel from across the globe, and represents an important part of my own search for self.

My mother’s family home can be found on Google Earth. It is recognized by the large roof of a 19th century bungalow, located just inside the periphery of what was, and still is Jabalpur Cantonment, a stone throw away from the landmark known as third bridge.

This post is dedicated in loving memory to my Aunt Geeta, and my many cousins spread across the globe.